Baby Marx at the Walker Art Center

Posted: August 11, 2011 | Project: Baby Marx | Tags: Baby Marx | Leave a comment »Baby Marx began as Mexican artist Pedro Reyes’ idea for a television sitcom in which puppet versions of key figures in the history of economics are brought back to life. Intended as a way to make the lofty and often distorted fundamentals of socialism and capitalism accessible to a broad audience, the piece has undergone several iterations since its inception four years ago. For his upcoming exhibition at the Walker, on view August 11, 2011 – November 27, 2011 Reyes will use Perlman Gallery and the entire Walker campus to begin filming a documentary version ofBaby Marx that examines its development to date as well as the complex issues with which it grapples. This past spring Reyes joined curators Bartholomew Ryan and Camille Washington to discuss the project in depth.

Camille: How did Baby Marx begin?

Pedro: I first had the idea for something I was working on in London, but it was too ambitious and was rejected. So, I put it in my drawer of unrealized projects. Then, in the lead up to the 2008 Yokohama Triennial in Japan, I was riding the Tokyo subway with Akiko Miyake, one of the curators of the exhibition, and I told her, “Well, I have this idea for a TV puppet show whose main characters would be Karl Marx and Adam Smith.” I like that there is a saying in Japan that says “A samurai doesn’t know the word impossible.” Miyake-san responded like is a true samurai, she said, “If that’s what you want, we’ll do it.” From there deciding what kind of puppets to use led to a super interesting exploration of the Japanese tradition of puppeteering.

Bartholomew: Why puppets?

Pedro: I think that puppets require a mastery and spontaneity not found in stop motion or animation. Also, puppeteering has been the historical equivalent to political cartoons in the performing arts. It is a form of critique similar to the ventriloquist or the court joker who was the only one who could make jokes in front of the king. The joker also often used some kind of doll or puppet. So, the puppet would spit out truths that would be unbearable from the mouth of a person.

Bartholomew: This was around 2007. Can you remember what it was about Smith and Marx that felt relevant at that moment?

Pedro: They didn’t feel relevant at that moment. This is the time before the credit crisis and the collapse of the markets. It felt like a subject which was precisely not fashionable. People would ask, “Why Marx?”However, there was something I wanted to find out not only about the state of the world, but also I wanted to know where I was standing in the political spectrum.

At a certain point in your life, you have this negotiation of your own ideas. When you first read Marx it makes so much sense, but then if you read Smith it also makes sense.Marx tells you “In order to have some rich people, others need to be poor” and then you read Adam Smith who tells you “Hey, what is all that equality business? You work more; you shouldn’t earn the same as the lazy one, right?” You may just ignore these voices but in my head I continued to hear these two people debating. So, I thought it could be interesting to stage this conflict. Here you have two philosophers who didn’t have the chance to meet in real life talking to each other. But also you have two conflicting sides of human nature. The task at hand was to choose fragments from Marx and Smith (among others) and weave a story, hopefully with the idea that it would become entertaining.

Camille: How does the Smart-O-Wave microwave oven that you used for the initial teaser and pilot of Baby Marx fit into the picture?

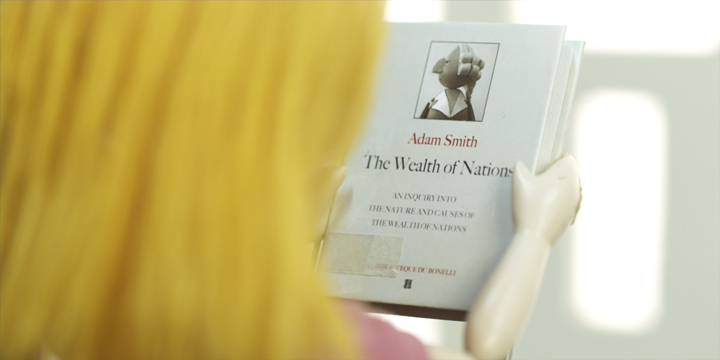

Pedro: Actually, the invention of the Smart-O-Wave was a turning point. It became a dimensional door that allowed me to bring any thinker into the story by placing the book they wrote in the oven. So by “defrosting” their thoughts they come back to life. It’s like a flying carpet, it can take you anywhere.

Camille: You speak a lot about mobile seminars and radical pedagogy. Is that something that also really underpinned the project in the early stages as much as entertainment did?

Pedro: Yes, Baby Marx was thought of from the beginning as a primer, or you could say Political Science 101. Sometimes you see the movie before reading the book, and for this subject puppets seemed the perfect treatment. Plus there was no Marx movie, no Adam Smith movie.

Bartholomew: The puppets were designed in collaboration with famous Japanese puppet maker Takumi Ota. I know the process was quite extensive. Can you talk about working together?

Pedro: Takumi Ota was the perfect match for this project, because he is a genius at leaving out everything that is not necessary and using the simplest forms. My obsession was the use of abstract shapes both in fine art and folk craft. In Japan, wood carved toys made in the wheel are very similar to Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus costume designs. So, fascinated by this extreme degree of abstraction, I started to design the characters using only platonic volumes; to cast the personality of a character in the simplest form. In fact the simplest form is a silhouette.

Bartholomew: This is when you made the Solids of Rotation studies…

Pedro: Exactly. This limitation was very productive. I gave Frederick Taylor a silhouette based in a hyperboloid, like a sand clock, because Taylor was obsessed with time management. With Marx’s it was obvious that I had to use his characteristic hairstyle which is like a trapezoid. Then, when you turn it into a solid of rotation it looks like a bit like samurai helmet. For Friederich Engels I took his long beard and made it into a spiral, like a party-blower; Che Guevarra has his beret and his goatee, so I made the head and the goatee like a top, and with the addition of the beret the solid of rotation looks like a hazelnut.

Camille: Did you work on the initial design alone or in collaboration?

Pedro: Takumi Ota made three-dimensional versions of drawings that I worked on in discussion with him. In the 1970s he designed characters for a series called Hyokkori Hiotan-jima, which means “the pumpkin island,” because the puppet heads were made with pumpkin seeds. The creative dialogue was great because I was thinking of what Ota San would like, almost trying to please him. It was almost a telepathic thing of trying to speak the same language, seeking the most extreme abstraction possible.

Bartholomew: You both passed these designs back and forth via the internet. He was in Japan and you were in Mexico for the most part.

Pedro: Yes, exactly. Due to the 15 hours difference Akiko and I met with Ota-san at 9pm, which would be his night. After seeing my drawing I would go to sleep and he would go on working all day making a clay model based on our conversations. Then, at 9 am in the morning (his night) we would meet again and review the progress. We went like this it a year and a half.

Camille: So, did you go there and finalize your designs with him or were they finalized by the time you arrived in Yokohama?

Pedro: There were several trips and meetings during that time. One of my favorite parts was the mechanics of how specific puppets operate. For instance, the Milton Friedman eyes turn and blink like dollar signs. Also, one side of his mouth is smiling and the other side is angry. His personality changes depending on which side of the camera it is facing. It is a way to show that two sides of capitalism: one charming and seductive, and other greedy and cruel.

[They laugh.]

Pedro: So, there are some interesting philosophical limits to the characters, but also the way they are built conditions their performativity.

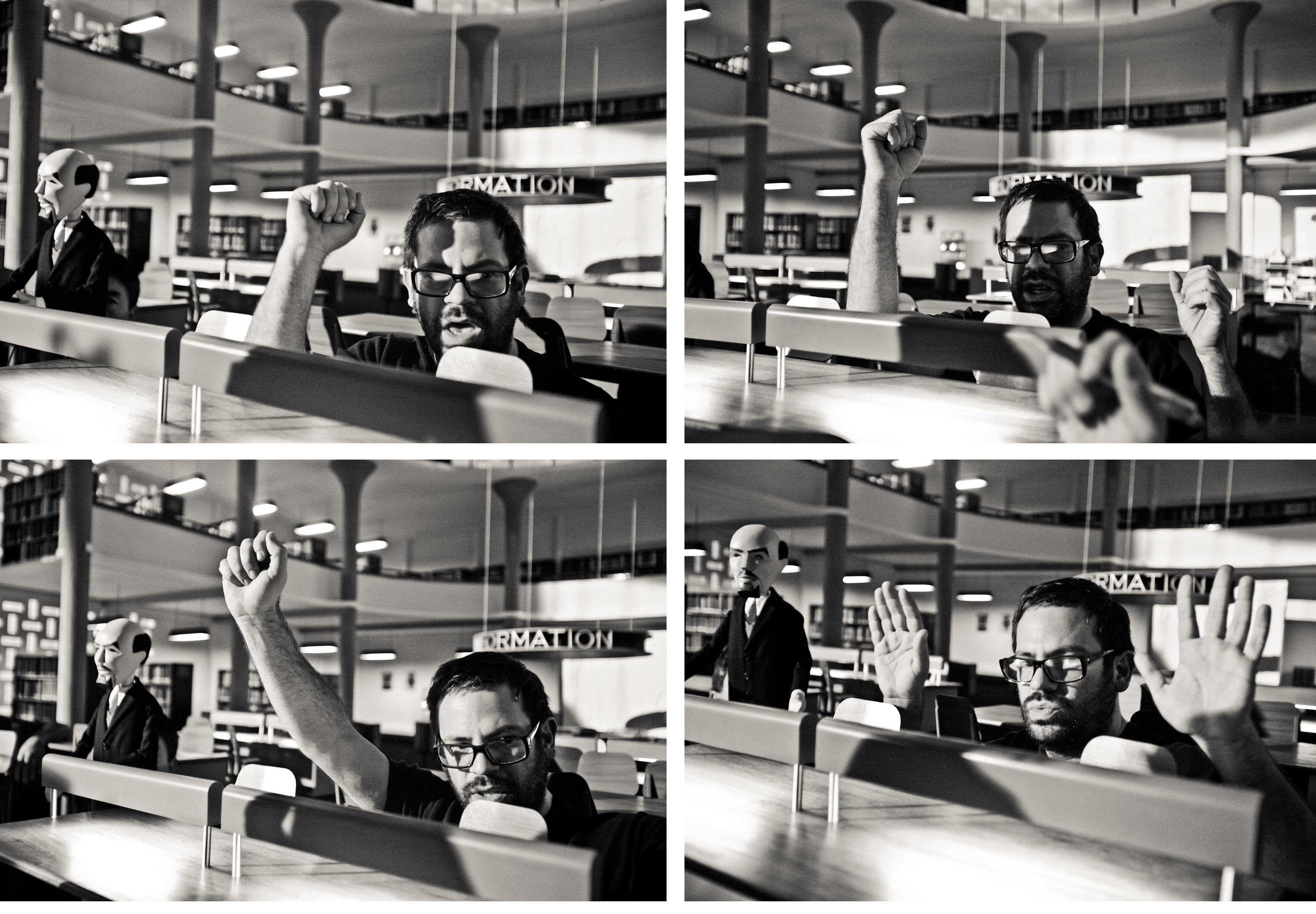

Camille: Before the pilot you made a teaser. In fact, you exhibited the teaser along with the puppets for Yokohama. Was the trailer an exercise in how the puppets ultimately would move and function and be filmed?

Pedro: Yes, in the beginning I met Ryo Ito who is an amazing puppeteer and became the leader of the puppeteers. He could take a shoe and make it perform Hamlet. So the movement design for each character was genius: the arrogant manners of Adam Smith, the tidy and nervous movements of Taylor. Again Frederick Taylor was obsessed with time management, so he would say, “OK, we’re going to make him swing like he’s a metronome for music.” Just perfect.

Camille: How does the type of puppet you use for Baby Marx differ from others?

Pedro: Rod puppets move very differently than glove puppets. Glove puppets like in Sesame Street look at the camera and open their mouths. In Japanese puppeteering the rapport between characters is conveyed more through the eye contact and with almost no mouth movement. Is much more subtle, and the intent is not necessarily to make you laugh. They can also perform on a darker note, which is something difficult with glove puppets. I like this style, which is not necessarily for delivering puns all the time.

Bartholomew: When you made the trailer, you had these gestures and a very distinct choreography for each of the characters. Camille and I were watching it again, and it’s very funny. It’s very enjoyable how each puppet moves and the ways in which they come into the piece.

Pedro: The election of the characters had to do with its potential for the plot. As much as you have the Marx and Engels duo, you have Adam Smith and Freddy Taylor, who are like the ideologist and the technocrat. The first is a persuasive courtesan and the second is an obsessive-compulsive. The characters fit in with certain roles. You need the archetype of Lenin in the revolutionary section, the Bolshevik giving grand speeches, but that rhetorical power has its counterpart in the pragmatic Che Guevara, who is willing to open (a loving or a fighting) fire. As the story unfolds Che Guevara ends up having a romance with Miss Lena, the librarian.

Bartholomew: There’s that moment at the beginning of the trailer where I think the titles are saying we’re living in a post-ideological age, and then the camera which is looking at this beautiful librarian zooms in and runs its gaze up her leg.

Camille: As she flicks her heel!

[They laugh.]

Pedro: I use the joke as a mechanism. Wittgenstein said that a serious philosophy book could only be written through jokes. The marvelous thing about a joke is when it presents the thesis and the antithesis in such an abrupt way that you synthesize it as laughter, a sort of airbag that cushions the collision of reality with your expectation of reality; the collision of ideology and realpolitik.

Camille: What is the time period for the original Baby Marx pilot?

Pedro: The story takes place in the present time. Crisisville, the city where the library is located, is a way to say that whatever we consider the status quo or “final state” of the world can change sooner than we expect. The last decade has been a good example. From 911 and the stupid wars that followed, the collapse of the economy, and today the revolutions in the Middle East, or the nuclear accidents in Japan. We have seen the map of the world shaken and transformed within a matter of hours…

Camille: I’m sure all this influenced your decision to set the entire Baby Marx narrative within a library as a place of ideas. Can you speak a little bit about the decision to use that setting?

Pedro: The library is a space which represents, on one hand, the post war idea of humanism. The capitals of the columns are like those in Le Corbusier’s Assembly building in Chandigarh, the tables and chairs are inspired by Jean Prouvé, the handrails are like Niemeyer and the lattice like México’s modernist Mario Pani. The atmosphere is reminiscent of a generic modernism that could belong to any country, like Korea, Brazil, Mexico, the U.S. or southern Europe. The fight to take control of the library also represents the current debate regarding the privatization of public services that used to be associated with the state. In general, it’s a caricature of the political-economic doctrines and models that decisions are based upon today.

Bartholomew: One thing that is really interesting about Baby Marx is that it’s a project that has emerged in stages where you re-imagine the project over time. Now we are coming up on a stage where the question really seems to be, “What are the terms of this piece?” This leads to wider questions about the intersections of ideology, entertainment, distribution, and so on. In terms of this journey was the pilot ever linked explicitly to Japan? Was it something that you imagined could be on Japanese television?

Pedro: Even if some of best talent for making puppets was in Japan it did not mean the best talent for writing was there because the humor in Japan doesn’t translate into the rest of the world. Or it translates but not in this register of political critique that you find in the United States, which has become in recent years one of the more sophisticated globally in terms of political satire. It seemed to be the most interesting challenge to reach or to try to be attractive to an audience in the United States because ideas have greater currency and potential for distribution.

Camille: When we were first talking about showing Baby Marx at the Walker, the project was still a pilot for a U.S. television show. Then a transition happened last year and you decided to make a feature film. Can you talk about that?

Pedro: TV and Film are two different markets. You cannot launch yourself into making a TV series without having a sale for a whole season. My producer Moises Cosio and I had very good meetings from different people from HBO, Sony, etc. They were interested, but none were ready to commit. I remember one “suit” who explained to us very clearly that “TV series are only a means to sell ads,” so I loved the contradiction of having a capitalist venture with a socialist content. However in TV, you can be on hold for an indefinite amount time. We realized that we didn’t need any approval to go ahead and do a movie on our own.

Camille: How did you go about drafting a script that would satisfy those demands?

Pedro: Well, during the writing process we discovered that the people who are best acquainted with the history of economics and politics are not funny. [Laughter] And the people who are funny as writers are not acquainted with the history of politics.

Bartholomew: That’s quite a predicament.

Pedro: Yes. I didn’t want to do something funny but superfluous, or to have something which is serious but boring. So, I have this rule of life that says “If you have to choose between A and B, do A and B.” Ergo, the decision to have both serious moments and funny moments. This is something you can do more easily in film than in TV. In TV the tyranny of the genre is harsher. If you are making a comedy you have to deliver one joke every 5 seconds.

So, with the film I also want to have pleasurable moments of seriousness because there you can have philosophers and political scientists comment on the subject. In between those moments of cleverness is where the opportunities for comedy arise, sketches, animation etc. That’s the stage we are in now.

Bartholomew: A while back when we were still thinking in terms of television the three of us visited PFFR, the television writing group that did the MTV2 puppet show Wonder Showzen using puppets a la Sesame Street but with outrageous content and approaches. It was super entertaining to listen to them just throw a few ideas around. Their instant suggestion was that Karl Marx and Adam Smith had to make love and have a baby. There was this sense that yes, this could be really funny, this could be really entertaining, this could be ridiculous and absurd but how hermetic it might become, in the sense that the “radical pedagogy idea” or any kind of instructive parallel to the comedy would likely have fallen away. In this sense perhaps moving towards the documentary structure which is, again, more open-ended and less resolved as an operating premise, feels like a natural move for the project.

Pedro: I think that one of the very interesting things about our meeting with PFFR was realizing that a variety show structure (episodic scenes with different approaches which they used in Wonder Showzen for instance) would be an ideal way to proceed. I realized that mixing the universe of real persons with the universe of puppets, and including devices such as animation, interviews, etc., we would make a more agile and diverse piece. The documentary is a little like a variety show in this sense. If you have too tight a structure it becomes harder to tell the jokes, and harder to tell the interesting facts. It’s not that the previous approach was wrong; it’s more than the addition of all the different approaches combined is much more powerful. So I do believe that, for the public, it will be much more interesting to have this embedded quality where you’re moving between universes.

Camille: Right, so the exhibition as Smart-O-Wave.

Pedro: Yes!

Camille: As curators, this development has led us to ask how we would articulate the exhibition to other people. And in asking that we discovered that the real way to talk about it is to be up front about that questioning, to see the Walker as a moment of reflection in the project, one that asks, “What is this thing?” What does it mean to bring together entertainment and ideology in some kind of popular format?

Pedro: One of the privileges of being an artist working with curators is having the room to ask these purely ontological questions. To question form and content entirely.

Camille: Yes.

Pedro: We have asked very important questions. How will be to shift from TV to film? How do we negotiate the exhibition space as a production space? How do we engage the public as participants in the critique of the content and of the medium? What is the design and function of the public events we are planning in relation to this new structure?

Basically, beyond asking what this project is, we are asking what the project is becoming.

Bartholomew: One of the questions that Baby Marx asks implicitly – something that mirrors PFFR’s suggestion that Smith and Marx make a baby together – is what could be a point where Adam Smith and Karl Marx could meet ideologically? Is Baby Marx about marking and pointing out the presence of the ideological inheritances we are all sifting through, or is it more interested in moving towards some kind of future model?

Pedro: Ideologies indeed intermarry in our minds and then give birth to our own thoughts which, obviously, inherit the beauties and defects of their parents. What interests me is to present these genealogies in progress, not as a final conclusion but as a tool. One such tool is called counterfactual history, which means: What if…? To imagine parallel histories that could have occurred. In this case, interesting arguments between two characters who did not have the opportunity to meet during their lives. An example of this is The Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu by Maurice Joly, which exposes the ideas of the state from two different perspectives. These two characters debate their doctrines and analyze human nature. Staging philosophical conflict is the aim of the project. Though, it never reaches a conclusion. It’s more about showing that instead of there being one right answer, there’s a myriad of answers, none of which should be embraced dogmatically. They should be used on a more ad hoc basis, according to the occasion and actuality. When we say, “OK, this is the truth and it should be applied in every case,” that’s when things go wrong.

Bartholomew: For some reason I once read a book on how to write day-time soaps for American network television, and they pointed out that the most durable storyline that can carry an entire run of a show over many years is that of a love divided, that it is the most engaging device and should never be resolved. The best storylines will always just toy with resolution.

Camille: So, Baby Marx as an ideological cliffhanger…

Bartholomew: Right.

Camille: That’s built into the system!

Bartholomew: Exactly!

Camille: There is no ultimate truth, no finality. It’s all ongoing. And so really the idea that this documentary is constructed in a similar way makes it really relevant to the ideas.

Pedro: Yes, I think that often documentaries are used also with a rhetorical purpose designed to drive you to some conclusions. I’m more interested to lead you to questions, than to drive you towards a dogmatic embrace of a particular idea. In the twenty-first century, we should read Marx like any other classic. However, we should examine the idea of capitalism as the hegemonic final model. That is, people assume that capitalism is a natural law, that the world simply functions that way, and that a different model of social organization is impossible to achieve. During the twentieth century, the United States demonized left-wing ideas in such an emphatic way that the word communism had the meaning that terrorism has today. All this had a very clear objective, which was to impose a transnational economic model under the name of “liberal democracy.” History is full of examples of crimes committed in the name of this paradigm.